Advanced Micro Devices is the world's second biggest CPU manufacturer. It is also one of the oldest; the company was founded in 1969.

From the start AMD made a wide range of electronic components, with an emphasis on memory and communications products. Many early AMD products were second-source devices made under license. As the company grew, it started to develop more of an emphasis on manufacturing its own designs, including the world's first maths coprocessor, a 64-bit add-on for the best-selling Zilog Z-80.

AMD began making X86 CPUs after signing cross-license agreements with Intel in 1976 and 1982. AMD made Intel-designed 8088 and 286 parts for several years and relations between the two companies were good, but the massive sales of 8088 and 286 chips eventually changed the landscape. Intel had become so wealthy that it could go it alone now; do without the production facilities of the second source makers like AMD and Harris, and simply build more plants of its own. And it was now so well-established that it did not need the extra respectability that second sourcing gives a part.

With the 386, the second source makers like AMD, NEC and Harris were frozen out. Intel wanted to terminate the second source agreement, AMD and Harris wanted to continue. According to Intel, the cross-license only applied to the 8086/8088 and the 286. According to AMD, it applied to all X86 CPUs. The dispute soon wound up in court and the litigation dragged through many appeals. In the end AMD was successful, but the final judgement was not handed down until many years after the case began.

By the way, notice how much more prone to litigation the CPU industry is than the hard drive industry. This is largely the result of market structure. Seagate (for example) knows perfectly well that it has no chance of crushing Maxtor or Western Digital the way that Intel attempted to crush AMD and Cyrix. Hard drive manufacturers (like manufacturers of most electronic components) tend to make voluntary cross-license agreements with each-other before the litigation starts, and compete in the marketplace instead of the courtroom. In any case, it's usually very difficult to be certain of exactly who invented what, because seperate teams of engineers tend to end up all working on the same sorts of problem. Half the time the engineers themselves don't really know if the solution is entirely their own or not. Intel, however, had such a massive share of the X86 market in those days that it was prone to thinking that it had a right to all of it, rather than just the ninety-odd percent it actually held. In fact, of course, most of the really innovative CPU design features came originally from the mainframe and workstation markets, having been pioneered by IBM, Cray, Sun, Hewlett-Packard, Digital, and others.

In the meantime, while the legal action went on, AMD designed its own 386, using Intel microcode for compatibility. The courtroom battles were far from over, but the AM386 was the single most significant event in the history of the PC as an affordable product for ordinary consumers. It was a huge success. With the breaking of the Intel monopoly, PC prices dropped by hundreds of dollars within a matter of months, and the AMD 386DX-40 became one of the best-selling CPUs of all time.

Flush with funds, AMD was able to start building what was then the biggest CPU factory in the world, Fab 25 in (where else?) Texas. After a slow start, the AMD 486 was again successful, particularly the DX/2-66 and the DX/4-100, as were AMD's communications and memory products and the AM29000 RISC CPU which, like the Intel RISC products of the same era, made no dent on the PC market but found a home in industrial systems and laser printers.

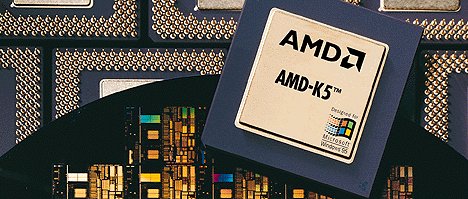

For its fifth-generation X86 chip, the K5, AMD cast off the apron-strings. The K5 owed nothing at all to Intel's Pentium and introduced many radical new design features. It was a technical masterpiece, and a production disaster. It was way too late and easily out-sold by both the Pentium and the Cyrix 6x86. Things looked grim for AMD with the K5 not performing and the 486-based 5x86 getting to the end of its life. The company was loosing money hand over fist and had its back against the wall.

In a controversial move — at the time many observers said a downright foolish one — AMD bought NexGen, a tiny CPU maker with nothing much in the way of assets bar a radical RISC-based X86 chip and a brilliant design team. History was to prove this a very wise purchase indeed. It took all of AMD's traditional tenacity and a healthy dose of revenue from successful non-CPU products to keep the company afloat while it digested NexGen, but the result was the excellent sixth-generation AMD K6, which was an immediate success.

The K6 could have been done better still had not AMD's then-new 0.35 micron production process given endless trouble — the same process, by the way, that was used to make the K5. For once, AMD's manufacturing ability was not up to the task of matching its design and marketing, and the first-genration K6 was always in short supply. It was only when AMD replaced its 0.35 micron plant with 0.25 micron process machinery that the company regained its usual manufacturing efficiency, just in time for the introduction of the revised and improved K6-2.The K6-2 was a great success, and although Cyrix and IDT got in for a small share too, it was primarily the K6-2 that cut Intel's US retail market share from 85% to just 54% in the northern summer of 1998.

This was also the time when Intel, so long the untouchable giant of the industry, began to make one bad decision after another, and entered a sustained technical slump that was to last right through until early 2002. But even an out-of-form Intel was a formidable opponent and AMD's all-conquering K6-2 soon faced renewed and much more capable competition from the Celeron-A.

It is fashionable these days to decry the old K6-2, and to conveniently forget all about the magnificent K6-III. The reality, however, is that they were highly competitive products in their day, and they made the Athlon possible: without the revenue stream that millions of K6 family CPUs brought in, AMD could not have found the cash to design the Athlon, let alone a second giant fab in Dresden.

This brings us to mid-1999 and the Athlon. There had been non-Intel chips that were performance leaders before, but never before had the challenger's ascendancy been unquestioned in every dimension, and not since the Z-80 had the reigning giant been unable to produce a quick response.

The Athlon had the fastest clock speed, the best integer performance, the strongest floating-point, and a lower price as well. It changed the CPU landscape in a way that no chip had ever done before. AMD pushed the speed grades up and up, and at one point was shipping 1000MHz parts in quantity while Intel were struggling to reach 600Mhz outside of low volume commercial samples. The Athlon ruled supreme through several incarnations, and it wasn't until late 2001 that Intel's Pentium 4 finally caught up to it.

As a player in the PC market, AMD has consistently taken the middle ground. It has never been as greedy and manipulative as Intel at its worst, nor has it ever gone in for the massive price cuts and borderline-truthful marketing that Cyrix sometimes stooped to. AMD is a consistent low-key achiever, and equally consistent with its long-term policy of always offering 25% better value than Intel for a similar product.

AMD pioneered the the now-common independent, clean-room X86 chip. Two or three other firms were in there in the early days of X86 development, but only AMD had the staying power to get the design right, get its manufacturing right, and produce in volume, all the while having to live with the massive disruption and crippling delays forced on it by the interminable legal battles with Intel. Cyrix would repeat the triumph just a year or two later on, but it was AMD that first brought competition (and thus lower prices) to the CPU industry, and AMD that is now the only remaining barrier against monopoly.